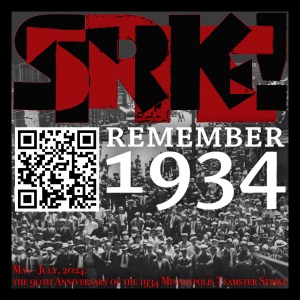

The Remember 1934 Committee plans a series of events to commemorate the 90th anniversary of the strikes, beginning in June and culminating July 27 with a picnic in Minnehaha Park.

This year marks the 90th anniversary of the 1934 Minneapolis Teamsters’ strikes. These strikes changed the course of history and the lives of tens of thousands of working people. They transformed Minneapolis from one of the country’s most notorious anti-union citadels into a “union town,” and they inspired labor organization from Fargo to Omaha, and Duluth to St. Louis. The story still resonates with the challenges faced by working people in 2024.

In the late 19th century a vibrant and diverse labor movement surged across Minnesota. Its ranks included native-born and immigrant workers employed as flour millers and barrel makers, railroad engineers, firemen, brakemen and track workers, garment workers and laundresses, horse and wagon drivers, building trades craftsmen, longshoremen and stevedores, skilled machinists and shop workers. They were affiliated with the Knights of Labor, the American Federation of Labor, the railroad brotherhoods, the Teamsters and the American Railway Union, and they created cooperatives, mutual benefit societies and a broad-based movement for the 8 hour day. These workers participated in the rail strikes of 1894, and they built political alliances with farmers. In the early 20th century, many took part in the creation of the Industrial Workers of the World and the Socialist Party, and they challenged some of the biggest businessmen in the U.S., including James J. Hill, Andrew Carnegie and Charles Pillsbury.

But bankers, businessmen and their political allies launched a powerful counter-offensive, seeking to eliminate unions through a “double-blacklist” – a refusal to hire union members and a refusal to extend loans to employers who bargained with unions. They created a new organization with a slippery rhetorical name, the “Citizens’ Alliance,” not only to implement their strategy but also to spin it as a defense of individual independence. They won accolades of employers’ organizations across the country. Minneapolis became an icon of non-unionism.

The Citizens’ Alliance’s success was devastating not just for unions but also for workers, who were disciplined, fired and blacklisted at the whim of employers. Although productivity rose with the introduction of new modes of work organization and technologies, wages lagged. Workers struggled to find economic security, and when they organized to challenge the Citizens’ Alliance, businessmen trumpeted the ideology of wartime “loyalty” and leveraged state government to limit workers’ gains. The reign of the Citizens’ Alliance seemed untouchable.

And then, in the winter of 1934, a small group of experienced, dedicated labor activists began to change the course of history. Several of them had been working in the city’s coal yards, earning miserable wages to handle and deliver coal to Minneapolis homes and businesses. Teamsters Local 574, with 75 members, initiated a strike on Feb. 7 that spread within three hours to 65 of the city’s 67 coal yards. They organized “inside” workers (warehouse and coal yards) and “outside” workers (drivers and helpers) together in an industrial strategy, and they ignored both the New Deal’s weak labor board system and the cautious advice of the Teamsters’ national leadership. They relied on cruising pickets, which shut the entire industry in the midst of a cold snap. Two days later, the coal employers offered a settlement, and the strike ended. Some 3,000 trucking and warehouse workers signed up to join Local 574. The inspiration was spreading.

In May, Local 574 called a larger strike across the city’s market district. Again, they linked inside and outside workers, ignored the labor board and relied on cruising pickets. Activists built an impressive infrastructure – a rented garage as a strike headquarters for dispatching mobile pickets, a soup kitchen and an infirmary, fully staffed by volunteers, many from the newly organized women’s auxiliary. They formed a “committee of 100,” mostly stewards from individual shops and warehouses, to make key decisions for the union, and a committee of the unemployed, not only to prevent strike-breaking but also to advocate for those without jobs. A network of farmers brought food for strikers and their families. They also secured the support of other unions and the Central Labor Council. The strike, which lasted 10 days, revolved around control of the streets. Despite police violence, the roving pickets were effective, and on May 25, employers offered an agreement, which the union accepted.

The ink had hardly dried on the agreement, however, when employers began to violate its terms. Over 700 complaints of discrimination were logged in June and early July. On July 17, Local 574 renewed its strike, this time with more than 10,000 participants. Another 35,000 workers engaged in a sympathy strike. The union mobilized with a new weapon, a daily strike bulletin (the first ever in the U.S.) called “The Organizer.” Once again, control over the streets was central to the strike, and there was more violence, even deaths, on both sides. A funeral procession for striker Henry Ness drew 100,000 sympathizers. The dispatch of the National Guard and the arrests and imprisonment of many union leaders could not bring the strike to an end. After President Roosevelt exerted pressure through the Reconstruction Finance Corporation, the Citizens’ Alliance finally yielded on Aug. 21, and employers were ordered to hold union elections, almost all of which ended in victories for Local 574 and new collective bargaining contracts. This broke the more than two decades’ reign of the Citizens’ Alliance.

Here begins the story of Minneapolis’ transformation into a “union town.” Some 10,000 workers not only won large raises, but they also got seniority provisions and a grievance procedure – a promise of justice in the workplace. Their success inspired other workers across the Midwest that they, too, could organize and improve their work lives. Rank-and-file Teamsters’ participation in the strikes – and their continuing participation in the life of the union – gave them a new awareness of their class position and solidarity with other workers. Their experiences also fueled their sense of their own capacity and power. They shared their new consciousness, and they embodied it in expressions of solidarity, supporting women workers in the Strutwear Knitting strike a year later, building of an interstate network of trucking workers and inspiring the unionization of packinghouse workers, timber workers, iron miners and steelworkers from Lake Superior to the Iowa border and beyond. Minneapolis had become a “union town,” and workers’ activism there was becoming a rising tide to lift all boats.

This situation persisted for half a century, for two generations. It became normal for workers throughout Midwest to earn a living wage with health benefits, vacations and pensions; to gain access to easier assignments as their seniority grew; and to expect a safe, respectful workplace. This was especially true in unionized workplaces, but non-union employers felt pressure to offer similar conditions. It was not a labor paradise, but many were able to buy cars and homes, send their children to college and enjoy retirement.

This changed abruptly in the 1980s and 1990s. Employers closed plants and sent manufacturing jobs abroad. They reorganized work via outsourcing and subcontracting. They chipped away at benefits, then wages, then unionization itself. While legislatures and judges weakened workers’ rights to picket, employers threatened those who still dared to strike with permanent replacement. The unionized cohort of the working class no longer enjoyed economic security, their ability to improve their own conditions diminished greatly and, increasingly, their role as trendsetters for all workers faded. By the turn of the 21st century, Minneapolis could no longer be called a “union town.” For that matter, neither could St. Paul or anywhere else in Minnesota and the Midwest.

But workers’ situations have not simply deteriorated; they have changed. Immigrants play an increased role in the economy and are more vocal, visible and significant in the labor movement. Public employees, white collar workers and retail, service, and fast-food workers have come to the fore. Educators and healthcare workers, from doctors and nurses to personal care assistants, see that unionization enables them to provide the care that brought them into their occupations in the first place. Members of Gen Z, struggling for economic security since the Great Recession, are bringing new energy into the labor movement. We are living in exciting times.

Now is a great time to look back at 1934, to learn how a wide range of workers changed the course of history and to consider how today’s workers might change this course themselves. A diverse group of activists, some of them descendants of the 1934 strikers, are organizing a series of events – an art exhibit, a picnic, film screenings and panel discussions – to curate a series of conversations between the past and the present. For details, visit rem34.ampmpls.com.

– Peter Rachleff is an emeritus professor of history at Macalester College and co-founder of the East Side Freedom Library in St. Paul.